Frisian mercenaries in the Roman Army. Fighting for honour and glory

- Hans Faber

- Mar 2, 2018

- 18 min read

Updated: Apr 12

After the Roman Empire had incorporated a big chunk of the British Isles in the first century, the empire needed a military force to defend their northern limes ('border'). Like elsewhere, they made use of mercenaries. Many Frisians, (still) living along the coast of present-day the Netherlands, joined the Roman army as mercenaries to fight in Britannia. So, what do we know about these early mercenaries?

The practice of hiring soldiers from a different nation is a common occurrence throughout history and across different regions. Even today, it is a well-known and fully accepted method of warfare. Consider the feared Gurkha regiments from Nepal, who swear allegiance to the British Crown, and the French Foreign Legion, which operates as part of the French army. We can also mention the African-American Harlem Hellfighters infantry regiments, who served anonymously for the U.S. Army in World War I and II.

According to the laws of war, apparently regulating warfare is not a contradictio in terminis; the Gurkhas and the Foreign Legionnaires are officially non-mercenaries because they are part of the national army at war. Probably, Frisian mercenaries, like other mercenaries within the Roman imperial army such as Hispanics from Spain, Tungri from Belgium and Saxons from the Elbe-Weser triangle, were seen as part of the army, too. Therefore, if we were to apply today's Geneva Convention, strictly speaking, the classification 'mercenary' probably would not be correct. Nevertheless, we use it here because they are all mercenaries, of course.

Whatever de jure the definition, and since during war everything is allowed de facto anyway, Frisian legionnaires might have had a similar reputation as the Gurkha's and the French Legionnaires of today. They are being paid less but fight fiercer. So, when you see them: run! We will come back to it below.

Frisii and Frisiavones

The first record of the Frisians, called Frisii or Fresones, by the Romans dates back to 12 BC. It is about how the Frisian tribes were allies during a battle against the Chauci tribe in the area of what is now the Wadden Sea coast of northwest Germany, roughly between the River Ems and the River Elbe. Like the Frisians, the Chauci were also not pacified. They were notorious pirates. Go to our blog post Our civilization — It all began with piracy for more details about the raiding Chauci and Frisians.

The Romans distinguished, besides other tribes living in the big delta, the Cananefates, the Frisii or Fresones, the Batavi, and the Frisiavones. According to soldier Pliny in his book Naturalis Historia, the Frisiavones lived on islands "inter Helenium ac Flevum". This is generally explained as the islands between the broader mouths of the River Meuse and the River Rhine. But scholars are still having disputes where to exactly pinpoint the civitas Frisiavones. We suggest just to describe it as the coastal section of the province of Zeeland south, part of the province of Zuid Holland, and parts up the River Meuse in the province of Noord Brabant. Based on archaeological finds, location Goedereede-Oude Wereld on the island of Goeree-Overflakkee, is a strong candidate for the former capital of the Frisiavones (Dhaeze 2019).

Furthermore, the tribe of the Frisiavones may be considered as Romanized Frisians (IJssennagger 2017). The part -avo means 'belonging to/descending from', so the people belonging to/descending from the Frisians (Neumann 2008). Ceramic found of the Frisiavones is of Frisian tradition. Thus, the Frisiavones the mannered part of the Frisians, and the Frisii being the independent, rude, barbaric part of the Frisii living in the north. Something that, of course, has all changed today. Archaeological research suggests that Frisiavones populated the area between the River Rhine and the River Meuse from the mid-first century, similar to the civitas Batavi.

That the civitas Frisiavones were subjects of province Germaniae Inferioris and of an administrative area or region called Frisavonum, is supported by a stone inscription found in 1958, in the Roman province Africa Proconsularis, present-day Tunisia. It is dated between AD 169-177. It concerns an inscription in honor of a certain procurator (i.e. administrator of a military district) named Q. Domitius Marsianus, with the text reading:

PROCVRATOR AVGVSTI AD CENSVS IN GALLIA ACCIPIENDOS PROVINCIARVM BELGICAE PER REGIONES TVNGRORVM ET FRISAVONVM ET GERMANIAE INFERIORIS ET BATAVORVM

Tunisia — By the way, in the year 1270 the Frisians would land on the coast of Tunisia again, but this time as fighters part of the Eighth Crusade under the banner of King Louis IX. Read our blog post Terrorist Fighters from the Wadden Sea. The Era of the Crusades to understand more about the atrocities committed by the Frisians during these campaigns.

As said, the tribe of the Frisians more or less lived in the area of present-day provinces Noord Holland, Friesland and (partly) Groningen. Curiously, a shrine dedicated to the idol Matres Frisiavae has been found at present-day Wissen in Germany. Wissen, a town halfway between the cities of Cologne and Frankfurt. In Roman sources the Frisians are also nicknamed transrhenana gens, meaning ‘people across the Rhine’.

The Frisiavones, part of the Roman Empire, had their own military unit, the Cohors I Frisiavonum, meaning first cohort of the Frisiavones. This cohort was deployed in Britannia. Frisiavones also were enrolled in special forces like equites singulares 'horse guards' and as corpore custos ‘bodyguards’ of the emperor. The Frisii were more individual entrepreneurs, and enlisted in the Roman army as individuals at first. From around 200 onward the Frisii formed their own military chapters, under the name cunei ‘unit’ Frisionum or Frisiorum and stationed at Hadrian’s Wall.

Job vacancies

The proximity of the Roman Empire also offered opportunities to the Frisian wildlings. One opportunity was to join the ranks of the imperial army, and fight in Britannia for wealth and glory. For about three centuries Frisians were recruited for the Roman army.

Traces of the Frisian men who had joined the legion, both the Frisii and the Frisavones, have been found at the English towns of Bicester, Burgh-by-Sands, Carrawburgh, Cirencester, Glossop, Hexham, Manchester and Papcastle. From, for example, the tidal marshlands in the north of the Netherlands they sailed to the present-day town of Domburg on the island of Walcheren, or to that of modern Colijnsplaat, both in the province of Zeeland. From here, they crossed the North Sea to the county of Kent in the southeast of England, maybe together with merchants trading in e.g. wine from Cologne or Trier in Germany, of which we know the trade was quite intensive. Of course, they would only make the sea crossing after having made offerings to the water goddess Nehalennia for a safe passage. Read more about the major importance of the island of Walcheren as a one of the big 'ferry ports' connecting the Continent with Britannia, in our blog post Walcheren Island. Once Sodom and Gomorrah of the North Sea.

Concerning the presence of Frisian legionnaires in Britannia, it is instructive to point out that Tuihanti tribesmen, of whom we know that they were deployed by the Roman army in Britannia too, have been interpreted as Frisians as well (Nijdam 2021).

Not only did Frisians serve in Britannia. Also more close to home along the limes 'border/border path' in what is now the Netherlands Frisians were deployed. During the period between around AD 70 and 220, the Frisians had no specific military unit or cohort with there own name, but were deployed in other units, like that of the Batavi. Batavi cohorts, in fact, might have consisted of also significant numbers of Frisians and Cananefates (Heeren 2020). Check the website Portable Antiquities of the Netherlands (PAN), a project inventorying all the finds of detectorists over the years, and which helps to gain a deeper insight in, among other, Frisians joining the Roman ranks.

Piracy — Besides joining the army as mercenary, the other opportunity the close proximity of Roman wealth offered, was plunder and piracy. The regions north of the River Rhine were heartlands of piracy. From here Germanic tribes raided the coasts of Britannia and of northern Gaul. Learn more reading our blog post Our civilization — It all began with piracy.

Before reading further about the presence of Frisian mercenaries in Britannia, we need to elaborate a bit on military vocabulary.

You will notice that often is referred to so-called cunei units. A cuneus was an auxiliary, small infantry or cavalry force of varying strength, named after the cunei-shape or ‘wedge-shaped’ offensive formation the force adopted in battle. The cunei forces were mainly restricted to non-allied tribesmen who offered their services as mercenaries. Again, parallels to today’s Gurkha’s and the French Foreign Legion as they are deployed at the front of battle too. The rough boys whose casualties are not been noticed by the public too much. You do not mess with them and, indeed, you better run. In a late-third-century ode to Emperor Maximian, it was worth mentioning that enslaved Frisians and Chamavi, a tribe living east of the Frisii, worked the land for the Romans. Testifying their former tough reputation to be subdued.

Time to list the documentation of Frisian mercenaries working for ancient Rome. These are altar stones, funerary inscriptions, memorial pillars, an imperial document, and diplomas:

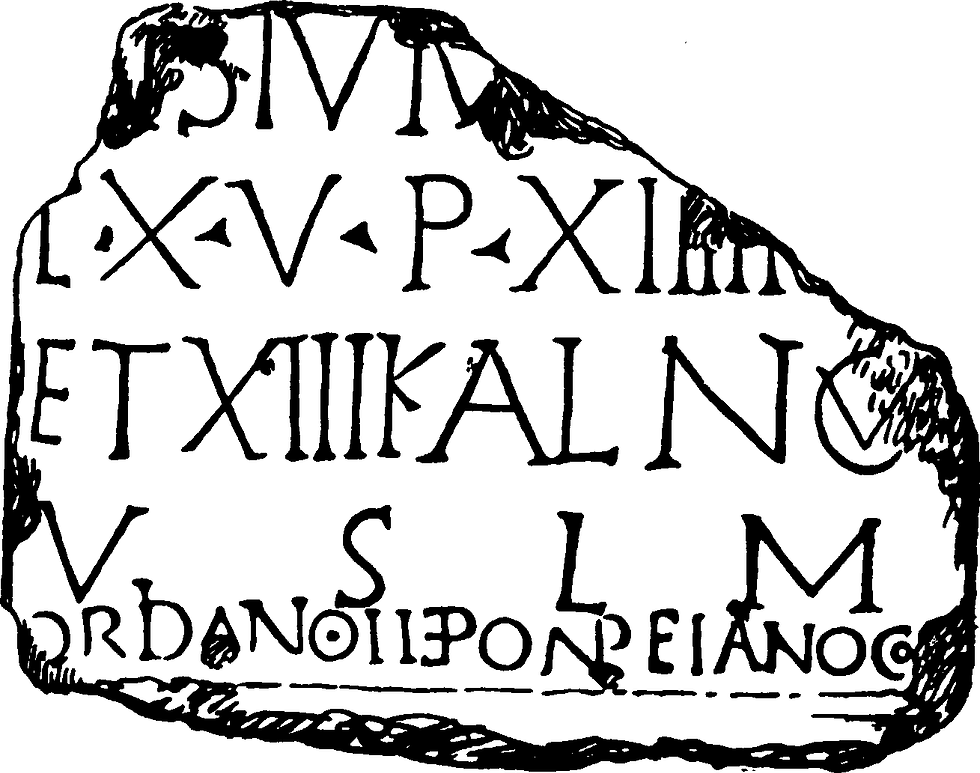

1. Fort Derventio Carvetiorum at Papcastle

[…] IN CVNEVM FRISIONVM ABALLAVE […] EX V P XIIII KAL ET XIII KAL NOV VSLM G II E PONPEIANO COS

"… to the cuneus of the Frisians of Aballava (present-day Burgh-by-Sands) … in accordance with his vow set this up on October 19 and 20 in the consulship of Gordian for the second time and Ponpeianus, gladly and deservedly fulfilling his vow." Altar stone AD 241.

nota — That this cuneus force came from the settlement Aballava, meant they had been stationed there before.

[…] EG AVG IN C NEVM FRISIONVM ABALLAVENSIVM P XIIII KAL ET XIII KAL NOV GOR II ET POMPEI COS ET ATTICO ET PREXTATO COS VSLM

"… transferred by (?) the Emperor's legate to the cuneus of the Frisians of Aballava (present-day Burgh-by-Sands), styled Philippian, on October 19 and 20 in the consulships of Gordian for the second time and Pompeianus and of Atticus and Pretextatus, gladly and deservedly fulfilled the vow." Inscription AD 242.

2. Fort Vinovia (Fort Binchester) near Bishop Auckland

[…] MANDVS EX C FRIS VINOVIE VSLM

"… Mandus veteran of Frisian Cuneus of Vinovia gladly and deservedly fulfilled his vow." Altar stone AD 43-410.

3. Fort Vercovicium (Fort Housesteads) near Hexham

DEO MARTI ET DVABVS ALAISIAGIS ET N AVG GER CIVES TVIHANTI CVNEI FRISIORVM VER SER ALEXANDRIANI VOTVM SOLVERVNT LIBENTES M

"to the God Mars the two Alaisagae goddesses and the divine spirit of the Emperor, the German tribesmen from Tuihantis serving in Frisian cunei formation, true servants of the Alexandrian, gladly and deservedly fulfil their vow." Altar stone ca. AD 222-235.

nota — Tuihantis is the present-day region of Twente in the Netherlands. Fort Vercovicium was part of Hadrian's Wall.

DEABVS ALAISIAGIS BAVDIHILLIE ET FRIAGABI ET N AVGN HNAVDIFRIDI VSLM

"to the goddesses the Alaisiagae, Baudihillia and Friagabis, and to the divinity of the Emperor the unit of Hnaudifridus gladly and deservedly fulfilled its vow." Altar stone ca. 222-235.

DEO MARTI THINCSO ET DVABVS ALAISIAGIS BEDE ET FIMMILENE ET N AVG GERM CIVES TVIHANTI VSLM

“to the god Mars Thincsus (thingsus) and the two Alaisiagae, Beda and Fimmilena, and to the Divinity of the Emperor the Germans. Tribesmen of Twente fulfilled (their) vow willingly and deservedly” (after Mees 2023). Pillar ca 222-235.

nota — The name Tuihanti refers to the region of Twente in the east of modern the Netherlands. However, these Tuihanti tribesmen have been interpreted by different scholars as Frisians (Nijdam 2021) or as tribesmen from Twente who joined the cavalry of the cuneus Frisorum (Mees 2023). Deo Mars Thincsus means 'god Mars of the thing'. Tiwas (also Tíwes or Tiwaz) was the god of the thing, also called ting, ding or þing 'people's assembly'. Mars of the thing must be interpreted as Tiwas of the thing. Tiwas is the same as the god Tuw, what was a supreme god of the Germanic believe. It is interesting to note that this pillar therefore not only testifies of Frisians presence in Britannia, but also happens to be the oldest written evidence of the thing (thincsus) anyhow, plus it was erected by Frisians!

In the German and Dutch languages, Tuesday is called after the thing, namely Dienstag and dinsdag, that refers to the day of the thing. The English and Frisian languages refer with respectively Tuesday and tiisdei to the god of the thing, namely Tiwas. If you want to know everything there is to know (we are trying to sell here) about the Germanic thing, the people's assembly, read our blog post Well, the Thing is...

nota — This inscription is considered one of the most important Germano-Roma epigraphic finds in Britain (Mees 2023).

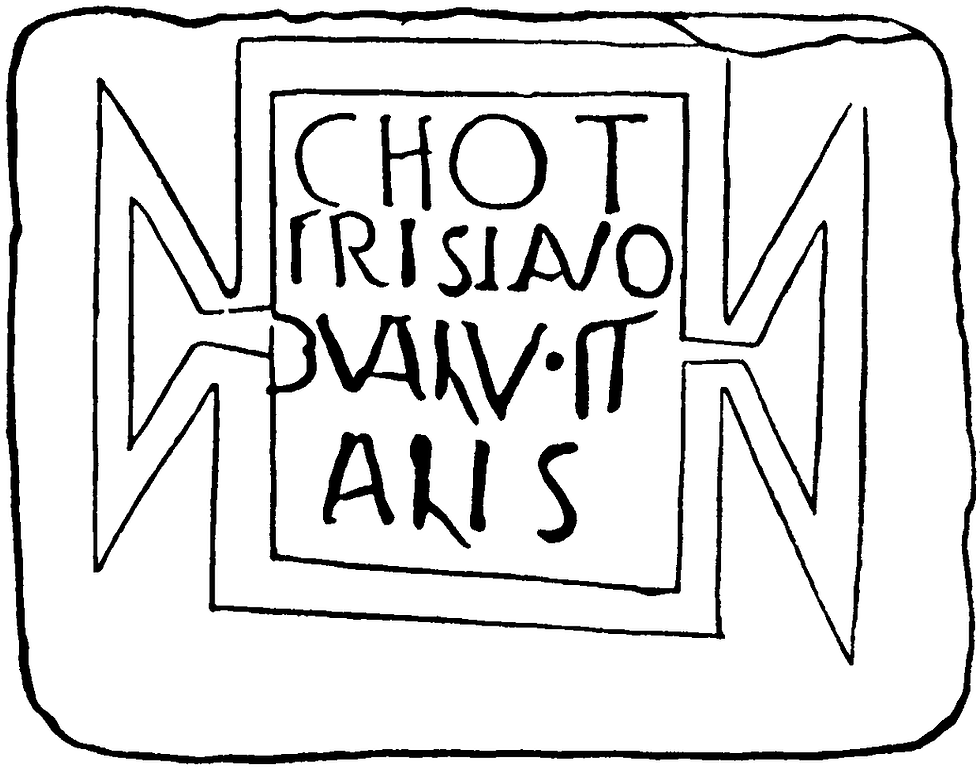

4. Fort Ardotalia (Fort Melandra) near Glossop

CHO I FRISIAVO VAL VITALIS

"from the First Cohort of the Frisiavones the century of Valerius Vitalis [built this]." Stone inscription AD 43-410. It is assumed fort Ardotalia has been built by the First Cohort of the Frisavones.

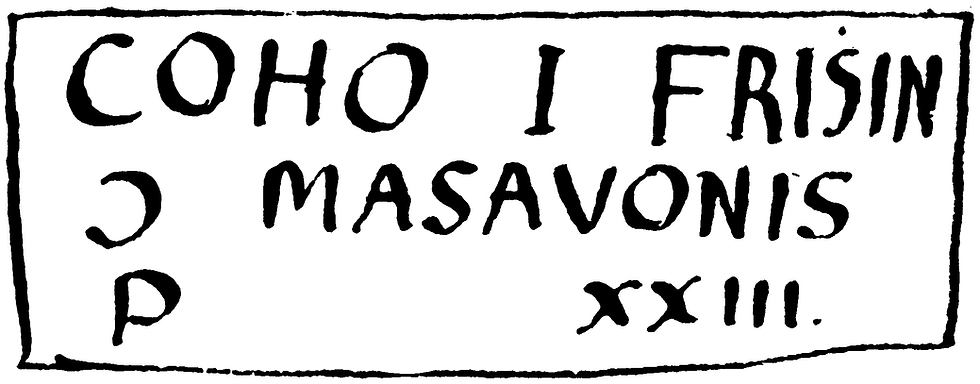

5. Fort Mamucium at Manchester

COHO I FRISIAV MASAVONIS P XXIII

"from the First Cohort of the Frisiavones the century of Masavo [built] 23 feet." Inscription building stone AD 43-410.

COHR I FRISIAVO QVITIANI P XXIIII

"from the First Cohort of Frisiavonum the century of Quintianus (built) 24 feet." Inscription building stone AD 43-410.

CVDRENI CHOR I RISIAV P [...]

"the century of Cudrenus from the First Cohort of the Frisiavonians [built] … feet." Inscription centurial stone AD 43-410.

nota — The latter inscription of Cudrenus cannot be definitely attributed to the First Cohort of the Frisiavones because it fails to mention the unit. However, its similarity to the three other inscriptions suggests that it refers to the Frisiavones (Galestin 2016).

6. Fort Brocolitia at Carrawburgh

DE CONVETI VOT RETVLIT MAVS OPTIO CHO P FRIXIAV

"to the goddess Convetina. Mausaeus, optio of the First Cohort of the Frixiavones, paid his vow." Altar stone AD 43-410. Fort Brocolitia was part of Hadrian's Wall.

7. Fort Corinium Dobunnorum at Cirencester

SEXTVS VALERIVS GENIALVS EQES ALAE TRHAEC CIVIS FRISIAVS TVR GENIALIS AN XXXX ST XX H S E H F C

"Sextus Valerius Genialis, trooper of the cavalry regiment of Thracians, a Frisiavone [Frisii] tribesman, from the troop of Genialis, aged 40, of 20 years' service, lies buried here. His heir had this set up." Tombstone ca. AD 45-75.

8. Diplomas

Eight military diplomas have been found concerning Frisian mercenaries in the Roman army. These diplomas was a proof that the soldier was honourably discharged from the army, and/or received Roman franchise/citizenship.

The diploma (nr. 1) found at Sydenham, London in England, dates from ca. AD 105. This diploma was issued by Trajan and mentions the First Cohort of the Frisiavones. They appear among other cohorts:

I FIDA VARDVLLORVM I FRISIAVONVM I NERVIORVM

The diploma (nr. 2) found at Delwijnen in the Netherlands, dates from ca. AD 116. This diploma was issued by Trajan and mentions the First Cohort of the Frisiavones also. The text of the diploma is reconstructed as follows:

AVGVSTA ET I (...)M ET I FRISIAVONVM ET (...) ET MENAPIO RVM(...) M ET III LINGONVM ET (...) ET IIII LINGONVM ET (...) ET SVNT IN BRITANNIA SVB (...)

The diploma (nr. 3) found at A-Szöny, current Komárom in Hungary, dates from AD 122. This diploma was issued by Hadrian and mentions the First Cohort of the Frisiavones also. The diploma mentions:

I FRISIAVON (and) I FRISIAVONVM

The diploma (nr. 4) found at Göhren in Germany, dated ca. AD 129-134. This diploma was issued to a common soldier, a Frisian veteran. The text of the diploma is reconstructed as follows:

(...) ALAE AVRIANAE CVI PRAEST (..) BASSVS ROMANVS EX GREGALE (...) LI FILIO FRISIO ET (...)INI FILIAE VXORI EIVS BATAVAE ET (..)ELLINAE FILIAE EIVS (...) FELICIS (...) ALCIDIS (...) PROCVLI (...) DAPHNI (...) AMPLIATI (...)

This Frisian soldier was enrolled in the Ala I Hispanorum Auriana, an auxiliary unit, under the command of Bassus from Rome. The Ala Auriana unit, mostly with recruits from Spain, operated in the Balkans, Austria and Switzerland. The owner of the above diploma had a Batavian wife and daughter, both their names ended with –ellinae.

Another diploma (nr. 5) testifying of Frisians has been found at Stannington, England, and dates from AD 124. It was issued by Emperor Hadrian. Yet another diploma (nr. 6), issued by Emperor Hadrian too, has been pieced together of two pieces. One piece found somewhere in the Balkans, and one piece found in London. It is dated AD 127. The diploma (nr. 7) found at the Roman fort near Ravenglass, England, was issued by Emperor Antoninus Pius in AD 158. The last diploma (nr. 8) was issued by the joint emperors Marcus Aurelius and Commodus, found in somewhere Bulgaria, and dates AD 178.

9. Notitia Dignitatum

The famous Notitia Dignitatum 'list of offices' dated early fifth century, also mentions a Frisian contingent deployed at Hadrian's wall. One unit deployed at Rudchester is called Cohors Prima Frixagorum, a Frisian cohort (Galestin 2016).

10. Emperor's bodyguards and horse guards

In Rome two funerary inscriptions have been found in the Monumentum Liberorum Neronis Drusi, a subterranean mausoleum attesting of Frisians in service of Rome, in this case corpore cvstos 'bodyguards' of Emperor Nero Drusus. These date from the first quarter of the century and read:

BASSVS NERONIS CAESARIS CORPORE CVSTOS NATIONE FRISIVS VIX A XL

Bassus bodyguard of Nero Caesar of Frisian [Frisii] origin lived forty years

HILARVS NERONIS CAESARIS CORPORE CVSTOS NATIONE FRISAEO VIX A XXXIII

Hilarus bodyguard of Nero Caesar of Frisian [Frisii] origin lived thirty-three years

Also in Rome, eight funerary inscriptions of equites singulares 'horse guards' have been found that are of Frisians, either Frisii or Frisiavones. These were inscription on tombstones. These eight inscriptions date to the second and (fewer) third centuries. We have listed the tombstone inscriptions in the annex to this blog post (see down below). Who knows, these riders venerated the Celtic goddess Epona, goddess of horses. The only foreign idol worshiped in Rome.

Lastly, there is a writing-tablet tabulae Vindolandenses, tablet of Chesterholm, dated between ca. AD 92-97. It contains several names of soldiers of the Cohort XIIII Batavorum, among them a certain bloke named Frissiaus.

We have put all the above locations of Frisii and Frisiavones ‘abroad’ during the Roman Period in a map for your convenience:

You want me on that wall—You need me on that wall!

Two of the forts mentioned are part of the famous Hadrian’s Wall, namely fort Brocolitia and fort Vercovicium. The latter better known as fort Housesteads. There were in total fifteen forts along Hadrian’s Wall, and around 10,000 soldiers were deployed along the wall. The wall was erected between AD 122 and 128, and was about 117 kilometers long.

Fort Housesteads is one of the major fortresses of the wall, with annex a civilian settlement or vicus called Virovicum. Actually, it resembles more a garrison town than a fortress. Interestingly, a distinctive form of pottery at fort Housesteads shows close parallels with that found in Frisia, especially the province of Noord Holland including the island of Texel. The pottery is only found in the vicus and not in the fort itself. The same Frisian pottery has been found at the fortress of Birdoswald too, a fortress west of Housesteads near Gilsland. Again, also next to the fortress outside its walls. The question arises whether the Frisian legionnaires at Housesteads and Birdoswald fabricated the pottery themselves, it was imported, or that their Frisian women accompanied them to Britannia and that they were responsible for the production. Some scholars speak of the ancient Frisian settlement near Housesteads inhabited by soldiers and their families (Mees 2023).

The last option might actually not be that strange. When we, for example, recall how the colonial Royal Netherlands East-Indies Army (KNIL) of the Netherlands functioned in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It was literally the same: women, or concubines, of the KNIL soldiers followed their men, and were housed in an adjacent settlement to the fort (Lanzing 2005). And women were ‘mobile’, too, in Roman times. It is an accepted theory based on archaeological research in the Netherlands, that the exchange between tribes happened through ‘marriage’ (exchange) of women. These women took with them their own techniques for pottery, thus explaining finds of so-called ‘foreign’ pottery (Nieuwhof 2016). Proof of women living in the vicus of fort Housesteads and of fort Birdoswald, however, has yet to be found.

The third inscription of the overview given above, mentions the numerus ‘unit’ of Hnaudifridi. A group of mercenaries at Hadrian’s Wall based at fort Housesteads. This was an irregular force, or actually more a gang, named after their Frisian chieftain Hnaudifridus, or in his native tongue Notfrid. Presumably, Notfrid was a Frisian chieftain and led a Frisian mercenary force. These irregular forces became a common practice in the third century onward. Whether these irregular forces would still be classified as non-mercenary units according to Geneva Convention, we do not dare to answer.

It is not sure whether this unit belong to the infantry or to the cavalry. Frisians did have horses at their homelands. In fact, tidal marshland is excellent soil to breed strong horses. A smaller breed than the Roman horses. Frisians horses of Late Antiquity until the Early Middle Ages only had a height of about 135 centimeters at withers. When Frisians were deployed in the cavalry, it is likely they rode Roman breed horses. Romans disapproved of the small Germanic horse. Some historians think the odd are the Frisians were deployed in the infantry (Savelkous 2016). Still, the odds are that Notfrid and his gang formed a cavalry unit (Mees 2023). More Frisians were based in the cavalry. For example, the Frisian Sextus Valerius Genialis from the fortress Corinium Dobunnorum at Cirencester (stone inscription nr. 7 above) was a horseman too. And in Rome eight funerary inscriptions have been found of Frisian horse guards (see Annex).

Know that Notfrid will probably be indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal of Frisia (ICTF) at the town of Aurich in the region of Ostfriesland, Germany. Read our blog post about his provisional indictment by the ICTF.

Nota I — Did you know that between 1504 and 1795, ancient Roman Law in its purest form was the applicable law in the province of Friesland? Check our blog post Medieval Migration Law. A matter of liability for more about this anomaly in European law practice.

Nota II — The term Germanic is an invention of the Romans. Actually, the tribes above the Lower River Rhine might have been Celtic or a mixture of Germanic and Celtic. The Frisians (both the Frisiavones and the Frisii) might have been this, including the two Frisian kings or local leaders Verritus and Malorix who travelled all the way to Rome in the year AD 58, to plead with Emperor Nero their case for the use of land bordering the limes north of the River Rhine. Read our blog post Barbarians riding to the Capital to claim rights on farmland to learn more about these two kings and the Celtic-Frisian connection.

Nota III — Well into the fifth century, the Romans made use of mercenaries from the coastal area of the Wadden Sea. We even have a name of one of them, namely ᚲᛋᚫᛗᛖᛚᛚᚫ ᛚXᚢᛋᚲᚫᚦI reading ksamella lguskaþi and meaning 'Deer Hunter'. Check our blog post The Deer Hunter of Fallward, and his Throne of the Marsh.

Nota IV — Credit featured image of this post by karakter.de.

Annex

Eight funerary inscriptions of equites singulares ‘horse guards’ have been found in Rome, which are of Frisians, either Frisii or Frisiavones. These were inscription on tombstones. The inscriptions date to the second and (fewer) early third centuries. The reconstructed but incomplete still difficult to interpret texts relating to Frisian mercenaries, read as follows:

DIS MANIBVS (...) EQVITI SINGVLARI AVGVSTI TVRMA V (...) NATION(...) NE FRIS(...) T FLAVIVS C(...) EQVES SINGVLARIS AVGVSTI FRATRI PIISSIMO (...)

DIS MANIBVS AVRELIO R(...) NATIONE FRISIAVO (...)

DIS MANIBVS T FLAVIO GENIALI EQVITI SINGVLARI AVGVSTI TVRMA LARCI PROCLINI NATIONE FRISAONI STIPENDIORVM XVIII VIXIT ANNOS XXX X(...) ROMANVS (...)

(...) TVRMA VRBANI NATIONE FRISIAVO VIXIT ANNOS (...)X XVII MILITAVIT ANNOS (...) X

DIS MANIBVS AVRELIO VERO EQVITI SINGVLARI AVGVSTI NATIONE FRISEO TVRMA AELI GEMINI VIXIT ANNOS XXX MILITAVIT ANNOS XIII AVRELIVS MOESICVS HERES AMICO OPTIMO FACIENDVM CVRAVIT

(...) NATIONE FRISAONI TVRMA (...) ANI (...) MILITAVIT ANNOS (INVS (...) I (...)

DIS MANIBVS (...) L (...) EQV (...) S (...) FRISIAVO (...) F AGRA (...) F CHIV (...) CAND (...) H (...)

DIS MANIBVS T FLAVIO VERINO NATIONE FRISAEVONE VIXIT ANNOS XX T FLAVIVS VICTOR EQVES SINGVLARIS AVGVSTI FRATRI DVLCISSIMO FACIENDVM CVRAVIT

Suggested hiking

We hikers would not be worth a penny if we would not point out there is a fantastic hike along Hadrian’s Wall, too: the Hadrian’s Wall Path. It is a national trail, and is 135 km long. So, an excellent hike for a week. With all the Frisian warfare history at this wall, we dare to consider it as a natural extension of the Frisian Coast Trail after you have reached the end of the trail at the town of Ribe in Denmark. Just cross the North Sea in western direction from there until you hit the shores of England. Or, do it the old way. Travel to the island of Walcheren in the southwest of the Netherlands, give some offering to the gods and sail with a ship to Kent in East England.

More walls and hiking paths along old walls can be found in our blog post Another brick in the wall. A love-hate relationship.

Further reading

Bosman, V.A.J., Rome aan de Noordzee. Burgers en barbaren te Velsen (2016)

Broeke, van den P.W., Pierenpaté? Fries aardewerk ten zuiden van de Nederrijn (2018)

Buijtendorp, T., De gouden eeuw van de Romeinen in de Lage Landen (2021)

Bunt, van de A., Wee de overwonnenen. Germanen, Kelten en Romeinen in de Lage Landen (2020)

Dhaeze, W., The Roman North Sea and Channel Coastal Defence. Germanic Seaborne Raids and the Roman Response (2019)

Galestin, M.C., Frisii and Frisiavones (2016)

Gelder, van J., Nieuwenhuis, M. & Peters, T. (transl.), Plinius. De wereld. Naturalis historia (2018)

Ginkel, van E. & Vos, W., Grens van het Romeinse Rijk. De limes in Zuid-Holland (2018)

Goldsworthy, A., Hadrian’s Wall. Rome and the Limits of Empire (2018)

Heeren, S., Grensoverschrijdingen. Romeins-Germaanse interactie (2022)

Heeringen, van R.M. & Velde, van der H.M. (eds.), Struinen door de duinen. Synthetiserend onderzoek naar de bewoningsgeschiedenis van het Hollands duingebied op basis van gegevens verzameld in het Malta-tijdperk (2017)

Huisman, K., De Friese geschiedenis in meer dan 100 verhalen (2003)

Hunink, V (transl.), Tacitus. In moerassen en donkere wouden. De Romeinen in Germanië (2015)

Looijenga, A., Popkema, A. & Slofstra, B. (transl.), Een meelijwekkend volk. Vreemden over Friezen van de oudheid tot de kerstening (2017)

Mees, B., The English language before England. An epigraphic account (2023)

Meijlink, B. & Silkens, B. & Jaspers, N.L., Zeeën van Tijd. Grasduinen door de archeologie van 2500 jaar Domburg en het Oostkapelse strand (2017)

Mijle Meijer, van der R.A., Scheveningseweg gemeente Den Haag. Archeologische begeleiding rioolvervanging (2011)

Neumann, G., Namenstudien zum Altgermanischen (2008)

Nieuwhof, A. & Nicolay, J., Identiteit en samenleving: terpen en wierden in de wijde wereld (2018)

Nijdam, H., Law and Political Organization of the Early Medieval Frisians (c. AD 600-800) (2021)

Lanzing, F., Soldaten van Smaragd. Mannen, vrouwen en kinderen van het KNIL 1890-1914 (2005)

Lendering, J., Romeinen in Velsen (2016)

Londen, van H., Ridder, T., Bosman, A. & Bazelmans, J., Het West-Nederlandse kustgebied in de Romeinse tijd (2008)

Mol, J.A., Vechten, bidden en verplegen. Opstellen over de ridderorden in de Noordelijke Nederlanden (2011)

Preskar, P., The Imperial German Bodyguard. The Roman emperors trusted foreigners more than their own Romans (2021)

RIB Online, Roman Inscriptions in Britain (website)

Rushworth, A., Housesteads Roman Fort — The Grandest Station. Volume I Structural Report and Discussion (2009)

Savelkouls, J., Het Friese Paard (2016)

Soenveld, J.P., Romeinen ronselden veel ‘Friese’ soldaten (2020)

Southern, P., Hadrian’s Wall. Everyday life on a Roman frontier (2016)

Stedman, H. & McCrohan, D., Hadrian’s Wall path. Wallsend (Newcastle) to Bowness-on-Solway (2006)

Stolte, B.H. (ed.), Germania Inferior. Untersuchungen zur Territorial- und Verwatungsgeschichte Niedergermaniens in der Prinzipatszeit (1972)

Tuuk. van der L., De Romeinse Limes. De grenzen van het Rijk in de Lage Landen (2017)

Vanderbilt, S., Roman Inscriptions of Britain (RIB), website

Vugts, T. (ed.), Varen op de Romeinse Rijn. De schepen van Zwammerdam en de limes (2016)

Weij, van der A., Deabus et Dis Communibus. Thesis on the religious identity of auxiliary soldiers on the northern frontier of Roman Britain (2017)

Comments